The Shadows that shape Nations

We all have things holding us back - lack of time, focus, discipline. They seem insurmountable until you name them precisely. As Alex Hormozi put it: "Fears disappear when you go from vague to specific." The visible obstacles are easy to find, even if hard to resolve. It's the invisible ones that are trickier - hard to find, yet often easy to resolve once seen.

In Jungian psychology, these invisible obstacles coalesce into "the shadow": the parts of ourselves we suppress and hope never see daylight. Even virtuous values cast shadows: "be generous to others" creates its dark twin, "never ask for anything yourself" - something that the poet Robert Bly called "the long bag we drag behind us." Over time, we bury anything deemed unacceptable into the vast unconscious, where it sediments into an unseen feedback loop guiding our every decision. The shadow is simultaneously a source of shame and creative potential. This is the paradox we must pierce.

How did the shadow come to be?

Somewhere early in childhood, when we started gaining a sense of autonomy and behaved in a certain way according to our innate desires, we were quickly disciplined by our parents, teachers, community and society at large. We were told 'this is good' and 'this is bad'. So we divided our selves. In this cultural process of socialisation, we categorised our traits into 'good' and 'bad'. The 'good' traits deemed acceptable by society were the ones we showcased to the world, whilst the 'bad' traits had to be locked away. This civilising process (a neccessary condition for social order) was then never questioned. The 'persona' we developed was the conformity archetype - the element of our Self that is made up of:- social norms, rules, expectations, roles etc - that make us 'good' and 'acceptable' to society. Its the highly curated linkedin profile, or the carefully crafted accent, or the 'nice guy'.

The shadow in contrast, is the 'bad' stuff that society told us to hide. Of course, it never disappeared - it just became hidden. Its the inferiorities we prefer to hide from ourselves and others. Its the anger we suppress, the envy we deny, the vanity that never ceases, the secret ambitions we daren't share, the hatred we bury. It's the stuff that we don't want to own up to. Its also the belief that 'lazziness is bad' and so we spend a lifetime grinding away at our jobs, our relationships, our dreams, because we are afraid of being seen as lazy.

The persona is the pretence we put on for ourselves and others, whilst the shadow is the unconsious part that actually drives our behaviour. This disconnect is the source of inner conflict and the reason we find neither peace nor fulfilment.

For me, a shadow that I carried for years (decades actually) was the belief that "standing out was bad" - reinforced by community, by my profession, by my culture. Of course, I covered it well for years, with a persona of seeking consensus, being obedient and doing things the "right" way. My ego never allowed me to truly contend with the shadow that was essentially, just built on shame. Instead my persona masked this shadow, but at a cost. The cost of not fulfilling my potential.

And this is the story of all of us.

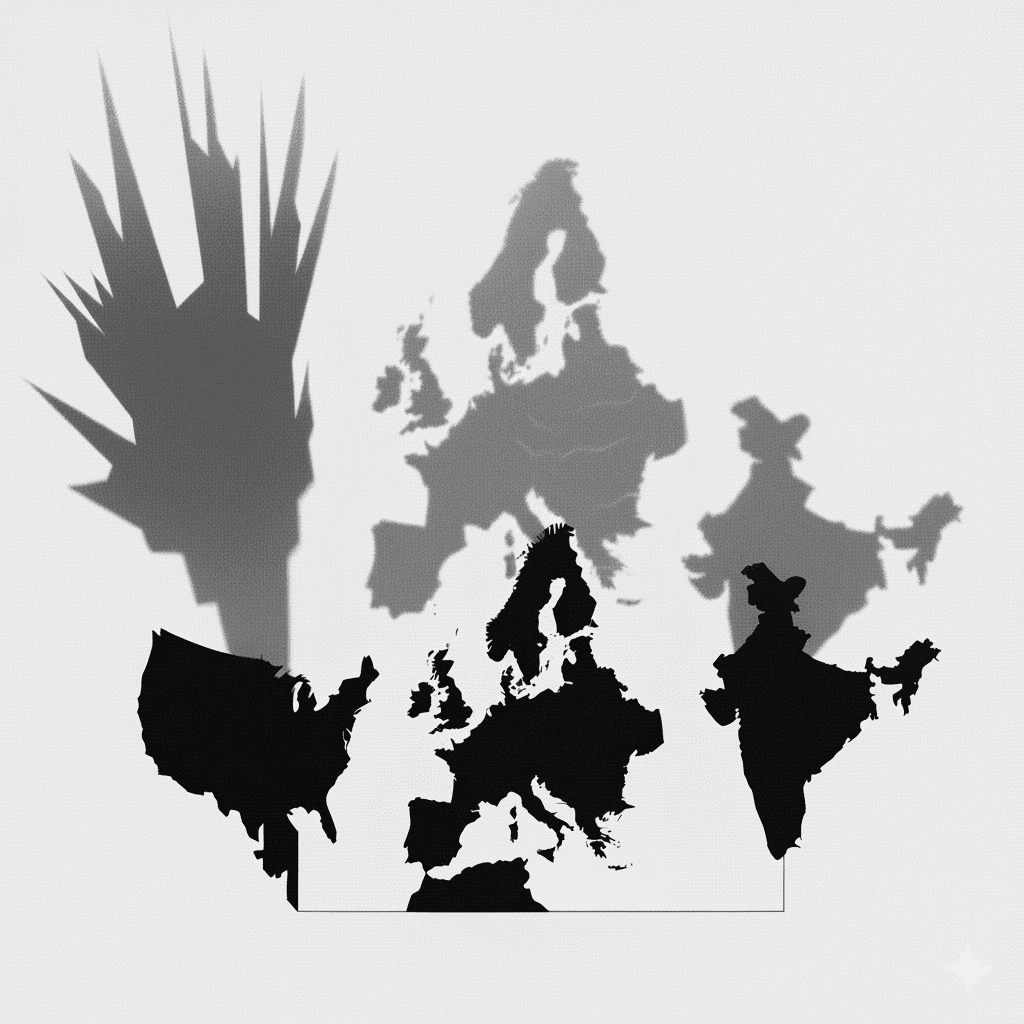

The Collective Shadow

Societies are no different. Like individuals, they too carry shadows: buried repressions, unexamined assumptions. You might call this "culture," but that's too vague. Culture is the mask. What lies beneath is more specific: constraint.

Societies - and more specifically, nation-states - are emergent properties of large swathes of people coming together. These emergent properties shape the culture (visible to all) and the shadow (hidden from all), which in turn re-shape the emergent properties of the society.

A note on terminology

For an individual, the shadow is the repressed part of the Self that the ego does not want to see. It opts to showcase the persona instead. For society, I call this hidden shadow the constraint. The society opts to showcase the culture instead.

Like the personal shadow that limited my personal potential, society's shadow (hereafter termed "constraint") limits its potential. Constraints are the guardrails of what's possible - the boundary conditions that shape a system's behaviour. Some are visible and explicit. But the most consequential ones are invisible, unspoken, unknown. Left unexamined, we remain at their mercy. "Until you make the unconscious conscious," Carl Jung wrote, "it will direct your life and you will call it fate." This is why we so often feel that despite doing so many great things, nothing seems to get fixed - the hypernormalisation of "more, new, better" that never moves the needle.

Constraints are necessary and inevitable limitations - but only if we consciously choose them to be so. Otherwise, they operate as hidden leverage points - shaping outcomes while remaining invisible to those within the system.

Healthcare Innovation - a case study in constraints

There is something interesting, even tragic, about healthcare's relationship with constraints. In a post-AI world, we will see the true colours of each nation's shadow.

Consider what's unfolding now.

In America, innovation moves at the speed of capital. It is frenetic, confident, allergic to friction. "Move fast and break things." The market will sort it out. The upside:- breakthrough capability, frontier innovation, wealth generation. But the shadow isn't the inequity that results from market failures - it's the unacknowledged belief beneath it: we do not trust the state to act in our best interests. The uber-confident upbeat demeanour of the average American is almost infectious for a boring Brit like me.

In India, where one doctor serves a thousands of patients who may never see a hospital, innovation is shaped by absence. Lean. Resourceful. Stubborn. The upside is genuine: frugal solutions that reach populations other systems ignore. The sheer scale of the country, the remoteness of villages and the jugaad mindset is a force to be reckoned with. I've seen it first-hand when I was working in India in 2013-14. Its a wonder to witness the directness of the approach. But the shadow isn't the scarcity - it's the internalized inferiority that scarcity has bred. The belief that "world-class" belongs elsewhere. That Indian innovation seems inherently makeshift. That frugality is destiny rather than choice. Whilst Modi's India has shown remarkable ambition, the shadow remains. It's no wonder the brain drain is a problem. Young Indian tech founders gain notoriety for being accepted on Y combinator.

In Europe, innovation proceeds like a deliberate, evidence-weighted, cautious process. The upside is safety, equity, universal access, and dare I say, trust. But the shadow isn't the slowness that ensues from regulation; it's the fear of individual agency beneath it. The belief that, in post-war Europe, unilateral decisive action is dangerous. That safety requires surrendering judgment to process. That consensus is always superior to conviction. As James C. Scott might observe, the European regulatory mindset has internalised legibility as virtue - the belief that what cannot be measured cannot be trusted. When I was building my first tech startup, I did one thing really well - I delayed and delayed and delayed. I delayed deployment because I was afraid of breaching some regulatory boundary. But that was just a cover for wanting consensus (which is distinct to product-market fit).

| America | India | Europe | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upside | Speed, breakthrough capability, wealth generation | Frugal innovation, scale, resourcefulness | Safety, equity, universal access, trust |

| Cause | Market incentives, VC culture, individualism, anti-communist ideology | Scarcity, scale, post-colonial underinvestment, necessity | 20th century trauma, social democracy, universal coverage mandates |

| Shadow | "The state cannot be trusted to act in our best interests" | "World-class belongs elsewhere" | "Decisive action is dangerous" |

| Downside | Inequity, access gaps, innovation for the wealthy | Quality ceilings, limited ambition, "good enough" as endpoint | Paralysis, innovation lag, delay as harm |

| Integration | Building collective responsibility into innovation | Claiming ambition without losing frugality's wisdom | Distinguishing wise caution from reflexive fear |

I make these generalisations hoping the reader acknowledges that these are a starting point and should be taken in the spirit of the argument rather than as literal truth. India, a country of 1.4 billion people is not homogeneous. I'd go as far as to say that these may just be my personal myopic views. But that's the point of this piece - to make us think deeper about our perceptions of ourselves and our societies. Perceptions are not facts, but they are powerful enough to shape reality.

Each nation-system has made its bargain with the future based on its constraints that have been shaped by its history. These three worldviews have been insulated from each other for decades, but they are about to collide.

Who will win the race?

The real question

The question of "who will win the race" belongs to a simpler world - one where technology transferred neatly from center to periphery, where America invented and the rest adopted.

The real question worth asking in this new multipolar and multi-ethic world is more unsettling: "who will win, which race?". By multipolar, I mean a world where geopolitical power is distributed and no external arbiter will declare a winner. By multi-ethic, I mean a world where there are many more ways of evaluating 'goodness' or the metric of 'winning' than just a single ideology.

Strategy documents, policy papers and manifestos will promise to win every race - the race of safety, of efficiency, of equity, of scale, of resourcefulness. But this utopian vision is simply the collective ego protecting itself from the uncomfortable truth that you can't have your cake and eat it too. In the immortal words of economist Thomas Sowell: "There are no solutions, only trade-offs."

When a nation can recognise its shadow-constraint and integrate it, it will start discovering which race it wants to compete in. The real question is not "who will win the race", but "what race will we choose to compete in?".

This is the work of strategic clarity. Let's explore what this means in practice.

Culture hides constraints - but should it?

Just like for an individual, where the persona masks the shadow, for society, the culture masks the constraints. We then justify it in the name of tradition, of history, of goodness, of virtue.

But in telling ourselves this story, we relegate our chances of making true breakthroughs: that constraints - not resources - determine what gets built, how it functions, and whether it succeeds. Constraints are the silent architecture of all innovation, in the same way as the shadow is the creative potential of the individual that is hidden from the conscious mind. Constraints are the invisible walls channeling effort into certain forms and away from others. We rarely examine them directly, because to do so would be to acknowledge the limits of our agency.

When we don't see them, we are beholden to them. When we see them, they are beholden to us.

Constraints exist on a spectrum of visibility. Some are unconscious - the unknown unknowns. Some are conscious but unexamined - the known unknowns. And some are fully illuminated - the known knowns. Knowing that constraints are the secret arsenal of innovation AND being fully illuminated about them is the work of strategic clarity.

Much like an individual's journey towards individuation (becoming whole) traverses an interim and very uncofrtable process of seeing the shameful aspect of ourselves, so too does a society's journey towards strategic clarity traverse an interim that is often very painful. But there does come a momenent when what was shameful becomes beautiful. Where it becomes a powerhouse of creativity and brilliance.

Culture should not mask constraints. It should illuminate them.

The shadow we carry

The constraints that shape innovation are not merely technical obstacles to be solved or policy gaps to be closed. They are the collective shadow of each society: the embedded assumptions, historical wounds, and structural compromises that remain unexamined because examination would require confronting uncomfortable truths about who we are.

Jung understood that integration, not elimination, is the path to wholeness. The shadow cannot be destroyed; it can only be brought into consciousness and reconciled with the self. The same is true for nations. A healthcare system that refuses to examine its constraints will continue to produce innovations shaped by those constraints without understanding why. A system that does the difficult work of integration, of naming what it has refused to see, gains something invaluable: the capacity to act with awareness rather than compulsion.

This is not abstract philosophy. It is practical counsel. In a multipolar world, the systems that have integrated their shadows will recognize that their innovations are not universal solutions but products of particular constraints. They will see other systems not as competitors to defeat or models to copy, but as partners whose different shadows produce different strengths. This is how complementarity emerges, not from diplomacy or trade agreements, but from the harder work of collective self-knowledge.

The work of strategic clarity

For individuals, integrating their shadow can come in different forms. "Knowing thyself" is something that most ancient traditions have espoused for millenia. For example, the Buddhist discipline of Vipassana - is about observing the body (a physical manifestation of the unconcious mind) as it is, without judgement. This is a form of shadow work that is about bringing the shadow into consciousness. From here, we find the shadow transforms into a source of wisdom and creativity.

The same is true for societies. A certain 'Vipassana' is needed for societies to confront their collective shadows. This is the work of strategic clarity.

In a multipolar, multi-ethic world, strategic clarity is not optional. It is the condition. The question is not whether nations will compete but on what terms - and with what degree of self-awareness. Those who understand their constraints will compete differently than those who do not. They will invest differently, regulate differently, and ultimately innovate differently.

This is the work that lies ahead: not the easy work of policy adjustment, but the harder work of collective self-examination. Understanding constraints is not a matter of commissioning reports or convening committees. It requires a kind of national introspection that political systems and electoral systems are poorly designed to produce. Constraints are defended by interests, obscured by ideology, mistaken for identity. To examine them honestly is to risk discovering that some of what we call "values" are merely rationalisations of limitations we lacked the will to change.

The work of strategic clarity for a society is not about commissioning reports or convening committees. It requires a kind of national introspection. It is a civilisational moment.

But, how accurate is what I say?

Doodling out

I often find myself sitting with a notepad and a pen, drawing out what's on my mind. Arrows, circles, boxes, lines - all to help me to see a it more clearly. I can be honest with myself, without the need to justify my thoughts or curate them for others.

At times I know where to go. Most of them time, I'm doodling trying to find my way. This 'doodling' out is my way of exploring the unknown. Its my way of discovering the shadow/constraints that are hidden from me. Its my way of gaining strategic clarity.

I make this point on 'doodling out' for two reasons First, the reader mustn't confuse this essay as some verifiable truth. It is not. It is a provocation, a 'doodling out' of my own thoughts and ideas that should be taken in the spirit of further exploration. As mentioed, 'doodling out' is an honest activity, even if what is doodled out is not pretty, palatable or verifiable.

Second, 'doodling out' is a way for collectives to discover their own shadow/constraints and integrate them in order to gain strategic clarity. This means, dialogue, debate, experimentation, iteration, questioning. It means being willing to be wrong, to be uncomfortable, to be challenged. It means being willing to change our minds. It means being willing to fail. It means being willing to learn. It means being willing to grow.

In this doodling, there are three corners that stack up against what I've written here. I offer these uncertainties not as hedges but as honesty.

The first corner: whether deliberate transformation is possible at all. We speak of nations "choosing" their futures as if collective systems respond to intention the way individuals might. But perhaps constraint - systems are more like weather than architecture - patterns emerging from countless interactions, too complex to steer, possible only to endure or adapt around. If this is true, the work is not strategic adjustment but something closer to seamanship: reading conditions, trimming sails, making the best of winds you did not summon.

The second corner: the question of time. A decade is a convenient horizon for thought pieces. It fits neatly into planning cycles and investment theses. But constraints do not respect our calendars. Some shift quickly when shocked; others resist for generations. Standing here, I cannot tell which changes are imminent and which are fantasies dressed as forecasts.

The third corner: who actually holds the lantern. If this examination is necessary, who undertakes it? Governments? Or will they skew things to get more votes? Markets? Whose vision extends to the next quarter. Perhaps no one leads. Perhaps the work proceeds the way understanding usually does - unevenly, through many hands, accumulating slowly until a new trajectory emerges that can no longer be ignored.

Perhaps only the reader of this essay holds the lantern.

References

- Bly, Robert. A Little Book on the Human Shadow (1988)

- Curtis, Adam. HyperNormalisation (2016)

- Gupta, Anil. Grassroots Innovation (2016)

- Jung, Carl. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (1959)

- Meadows, Donella. Thinking in Systems (2008)

- Radjou, Navi et al. Jugaad Innovation (2012)

- Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State (1998)